Escaping Swampland: Why Healing the Body Means Returning to High Carbs, and Limiting Fat

Across Evolution, Carbs Have Always Been The Foundation Of Human Energy — And Today’s High-Fat/High-Carb “Swampland” Is Entirely New

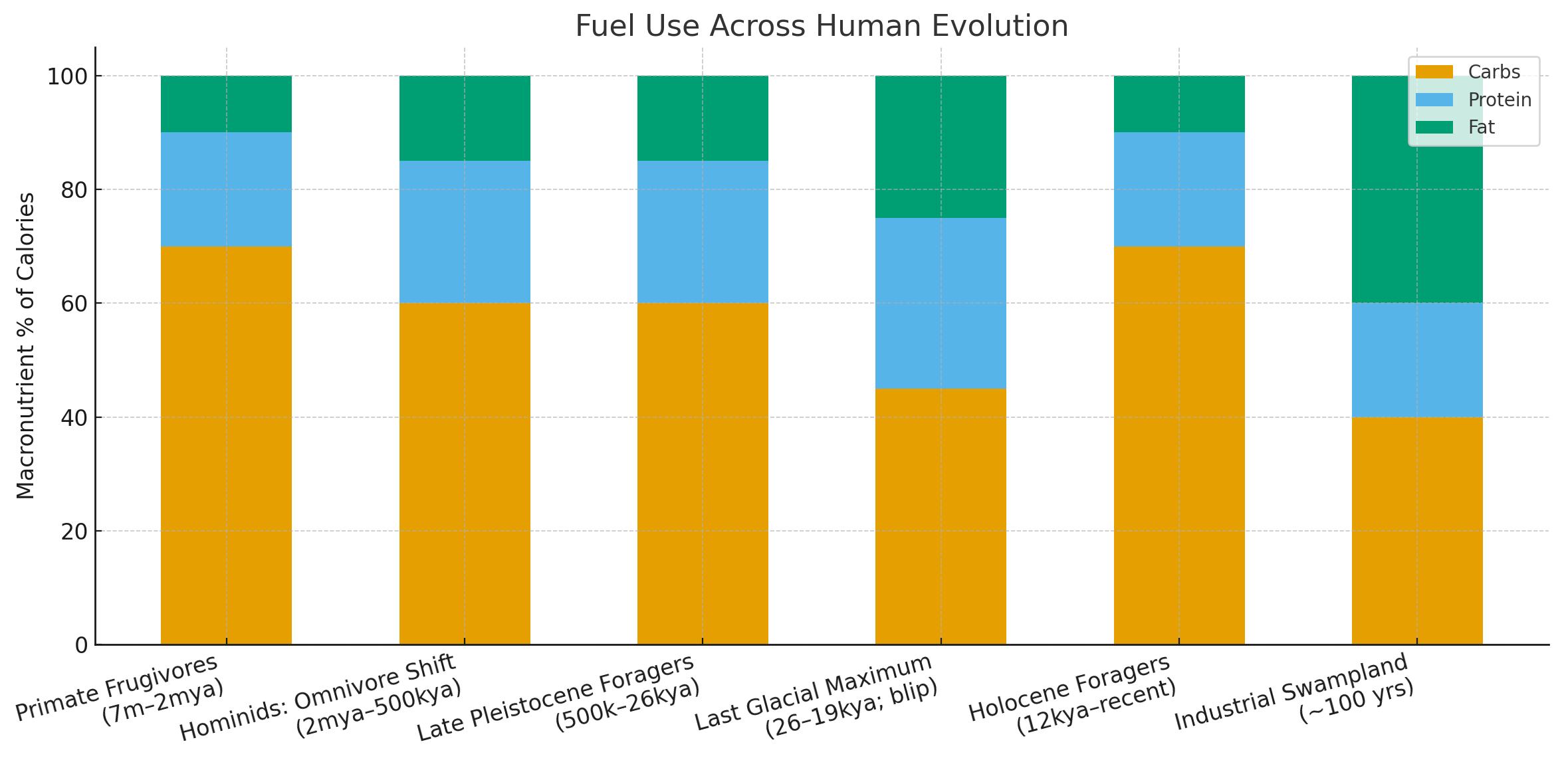

Modern humans are drowning in what Denise Minger calls Swampland nutrition — the deadly combination of refined fats and refined carbohydrates eaten together. Think of chips, donuts, fries, pastries, pizza, and ice cream. These foods didn’t exist in nature. For seven million years of primate and human evolution, we either ran on carbs or on fat — but never equal amounts of both at once, and never with over half the fat coming from seed oils. This distinction matters for metabolism, thyroid health, and body composition today.

The Evolutionary Fuel Story

Our story begins with our primate ancestors. For roughly 7 million years, chimpanzees, bonobos, and early hominins were overwhelmingly fruit eaters. Their diets centered on fruits, tubers, and other carbohydrate-rich plants, with protein from leaves and insects and modest amounts of fat from fruit seeds and the natural byproducts of fermenting fiber. For more than 90% of our evolutionary history, humans and our relatives were fundamentally carb-burners.

Around 2 million years ago, the first biped hominids (members of the genus Homo) began to emerge from the trees and walk on two legs. This is when a true dietary shift occurred: from being mostly frugivores to becoming omnivores. These early hominids began actively consuming animals — not just insects, but scavenged and hunted mammals. This added more protein and some fat to their diets, though it’s important to note that fat was still limited. Most wild animals are relatively lean, with body fat percentages ranging from about 4–7% in small to medium animals, and only slightly higher in certain larger species.

During the Ice Ages, especially in northern latitudes, humans occasionally encountered (and learned to hunt) megafauna such as mammoths, mastodons, and giant bison. This was largely during the last Glacial Maximum, starting 26,000 years ago. These animals carried somewhat higher fat reserves, especially seasonally, and they provided a crucial energy source in environments where plant foods were scarce. But this period of heavier reliance on animal fat was a short blip in evolutionary time, not the norm. Even then, the majority of humans lived closer to the equator, where tubers, fruits, and honey remained reliable staples.

By about 12,000 years ago, most of the megafauna had gone extinct. Fat-rich prey largely disappeared, and humans turned back toward plants for the bulk of their energy. Foragers and early farmers relied heavily on tubers, palm starch, fruits, honey, and eventually grains. Fat and protein intake fell, and carbohydrates once again became the foundation of the human diet. Agriculture locked this in further. For most of recorded history, humans were primarily carb-burners.

Only in the last 100 years did something truly novel appear: industrial Swampland foods. For the first time, humans combined high fat and high carb simultaneously. Refined flour and sugar mixed with industrial seed oils created the metabolic swamp we live in today. Modern diets now feature unusually high fat intake — much of it unstable polyunsaturated oils — alongside refined, nutrient-poor carbs. Protein has shrunk, and metabolism has slowed.

Why Swampland Breaks the Human Metabolism

Our mitochondria handle one main fuel stream at a time. When both carb and fat are high, insulin pushes carbs into cells, but fat oxidation stalls. Excess fatty acids — especially linoleic acid and other unstable PUFAs — flood the bloodstream and compete directly with glucose at the mitochondrial level, a phenomenon known as the Randle Cycle. This competition blocks glucose oxidation, leaving sugar trapped in the blood while cells are forced to rely on fat. The mismatch creates insulin resistance and keeps blood sugar elevated. Eventually, the pancreas overshoots with extra insulin, driving blood sugar down too far and triggering reactive hypoglycemia — the shakiness, anxiety, and fatigue so many people feel after eating Swampland foods. Over time, this chronic tug-of-war between fat and carbs damages mitochondria, suppresses thyroid hormone action, and locks in long-term insulin resistance. The result is a cascade toward obesity, low body temperature, infertility, depression, and chronic fatigue.

In contrast, carb-dominant diets — low fat, high carb, adequate protein — keep the thyroid humming, temperatures warm, and metabolism high. When fat is kept low, glucose flows freely into the cell without competition from fatty acids. This lowers the burden on insulin, restores metabolic flexibility, and reverses the mitochondrial gridlock of the Randle Cycle. Instead of swinging between high blood sugar and reactive hypoglycemia, the body maintains a steady supply of fuel to the brain and muscles. The thyroid responds by converting more T4 into active T3, raising body temperature and stabilizing mood, sleep, and energy. Over time, this translates into more resilient hormone balance, easier fat loss, and a metabolism that runs at a higher “idle speed.”

By contrast, fat-dominant diets can work short-term — especially during food scarcity, when survival depends on stored body fat. But when pursued long-term, the cost becomes clear: thyroid conversion slows, reproductive hormones drop, body temperature cools, and energy output declines. The body is forced into conservation mode, trading short-term survival for long-term vitality. This is why so many people on extended keto or carnivore notice hair loss, menstrual irregularities, PMS and menopause symptoms, muscle aches, constipation, low libido, fatigue, headaches, insomnia, or slowed fat loss despite strict discipline. It’s not a failure of willpower — it’s the physiology of a body running on the wrong primary fuel.

Why High-Carb, Low-Fat Is the Healing Path Now

For people coming out of years of keto or carnivore, the damage is often visible. They experience suppressed thyroid function with cold hands and feet, low body temperatures, and fatigue. Insulin resistance persists, fueled by stress hormones and PUFA-rich fat stores. Many struggle with body composition despite their discipline.

The way out isn’t to double down on fat. It’s to return to our evolutionary baseline: carbs as the primary fuel, with fat kept low enough to force the body to oxidize carbohydrate efficiently.

Shifting back to carbs has multiple benefits. Carbs stimulate T3 production and rebuild metabolic rate. Very low-fat, high-carb eating reverses insulin resistance faster than any other approach. Glucose availability supports reproductive hormone balance, while higher carb intake with adequate protein preserves muscle and promotes fat loss. In short, it rebuilds metabolism at the cellular level.

Practical Application

The healing path is simple. Keep carbohydrates high, sourced from fruit, honey, juice, sugar, tubers, and properly prepared grains. Keep fat low while strictly avoiding PUFA from seed oils. Maintain protein at adequate levels by prioritizing lowfat dairy, lean meat, gelatin, and collagen. Over time, this allows the body to burn off old PUFA stores and restore efficient carb metabolism.

The Big Picture

For seven million years, humans and our primate cousins thrived as carb-burners, with only a brief Ice Age detour into fat-burning thanks to megafauna. What we never adapted to is the modern swamp: high fat and high carb together. If you’re recovering from keto or carnivore, struggling with insulin resistance, thyroid issues, or stubborn weight, the solution is not to double down on fat-burning. It’s to reclaim your natural carb-fueled metabolism and escape the swampland for good.

Healing the metabolism starts by simplifying fuel. Stop drowning in Swampland. Return to carbs, lower fat, and watch your body remember how to thrive again.

References

Lee-Thorp, J. & Sponheimer, M. (2006). Contributions of stable isotopes to understanding diet and ecological adaptation of early hominins. Journal of Human Evolution.

Richards, M. & Trinkaus, E. (2009). Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. PNAS.

Wood, B. & Hawkes, K. (2017). Human evolution: Dietary ecology. Annual Review of Anthropology.

Krigbaum, J. (2003). Reconstructing human subsistence with stable isotopes in tropical contexts. Asian Perspectives.

Roberts, P. & Petraglia, M. (2015). Palaeolithic adaptations in tropical forests. Journal of Human Evolution.

Hill, K. & Hurtado, A. (1996). Aché Life History: The Ecology and Demography of a Foraging People. Aldine de Gruyter.